About sbpy¶

What is sbpy?¶

sbpy is an astropy affiliated package for small-body planetary

astronomy. It is meant to supplement functionality provided by

astropy with functions and methods that are frequently used in the

context of planetary astronomy with a clear focus on asteroids and

comets.

As such, sbpy is open source and freely available to everyone. The development

of sbpy is funded through NASA Planetary Data Archiving, Restoration, and

Tools (PDART) Grant Numbers 80NSSC18K0987 and 80NSSC22K0143, but contributions

are welcome from everyone!

Why sbpy?¶

In our interpretation, sbpy means Python for Small Bodies - it’s

the simplest acronym that we came up with that would neither favor

asteroids nor comets. That’s because we equally like both!

sbpy is motivated by the idea to provide a basis of well-tested and

well-documented methods to planetary astronomers in order to boost

productivity and reproducibility. Python has been chosen as the

language of choice as it is highly popular especially among

early-career researchers and it enables the integration of sbpy into

the astropy ecosystem.

What is implemented in sbpy?¶

sbpy will provide the following functionality once the development

has been completed:

observation planning tools tailored to moving objects

photometry models for resolved and unresolved observations

wrappers and tools for astrometry and orbit fitting

spectroscopy analysis tools and models for reflected solar light and emission from gas

cometary gas and dust coma simulation and analysis tools

asteroid thermal models for flux estimation and size/albedo estimation

image enhancement tools for comet comae and PSF subtraction tools

lightcurve and shape analysis tools

access tools for various databases for orbital and physical data, as well as ephemerides services

The development is expected to be completed in 2024. For an overview of the progress of development, please have a look at the Status Page.

Additional functionality may be implemented. If you are interested in

contributing to sbpy, please have a look at the contribution guidelines.

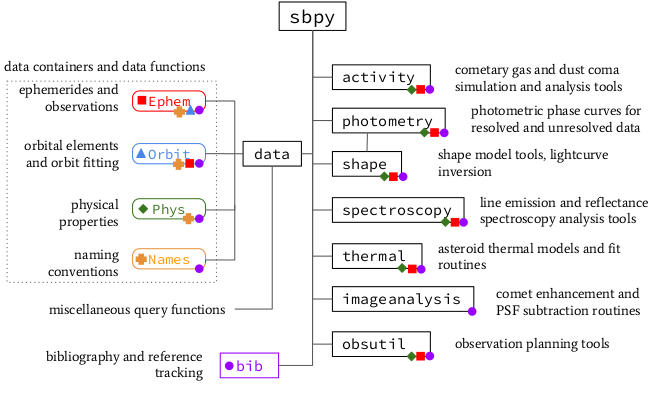

Module Structure¶

sbpy consists of a number of sub-modules, each of which provides

functionality that is tailored to individual aspects asteroid and

comet research. The general module design is shown in the following

sketch.

sbpy design schematic. Modules are shown as rectangular boxes,

important classes as rounded colored boxes. The left-hand side of

the schematic is mainly populated with support modules that act as

data containers and query functions. The right-hand side of the

schematic shows modules that focus on small body-related

functionality. Colored symbols match the colors and symbols of

classes and modules they are using.¶

The functionality of version 1.0, which will be finalized in 2024, is detailed below. Please refer to the Status Page to inquire the current status of each module.

sbpy.data¶

The data module provides data containers used throughout

sbpy for orbital elements (Orbit), ephemerides

(Ephem), observations (Obs), physical

properties (Phys), and target names

(Names). Instances of these classes are used as input to and

output for a wide range of top-level functions throughout sbpy,

guaranteeing a consistent and user-friendly API. All classes in

data provide query functions to obtain relevant information

from web-based services such as JPL Horizons, Minor Planet

Center (MPC), IMCCE, and Lowell Observatory, providing orbital

elements at different epochs, ephemerides, physical properties,

observations reported to the MPC, (alternative) target identifiers

etc.

Additional functionality of data includes an interface to the

orbit fitting software OpenOrb and an interface to SPICE for offline

ephemerides calculations using SpiceyPy, for which we will provide

utilities tailored to the needs of the small body community. Examples for how to use sbpy with ephemerides calculation package PyEphem and orbital integrator REBOUND (Rein and Liu 2012) will be provided as notebooks.

data also provides a range of other useful module-level

functions: image_search

queries the Solar System Object Image Search function of the

Canadian Astronomy Data Centre, providing a table of images that

may contain the target based on its ephemerides. sb_search uses

IMCCE’s Skybot; given a registered FITS image, the function will

search for small bodies that might be present in the image based on

their ephemerides. pds_ferret queries the Small Bodies Data

Ferret at the Planetary Data Systems Small Bodies Node for all

existing information on a specific small body in the PDS.

sbpy.activity¶

The activity module provides classes for modeling cometary comae, tails, ice sublimation. We have implemented the Haser gas coma model (Haser, Haser 1957), and a Vectorial model is planned (Vectorial, Festou 1981). Some parameters for commonly observed molecules (e.g., H2O, CO2, CO, OH, CN, C2), such as photo-dissociation timescale and fluorescence band strength, are included. The gas coma classes can be used to generate aperture photometry or a synthetic image of the comet.

For dust, we have simple photometric models based on the Afρ and εfρ quantities (A’Hearn et al. 1984; Kelley et al. 2013). A syndyne/synchrone model (Syndynes, Finson & Probstein 1968; Kelley et al. 2013) is planned.

The activity module includes LTE and non-LTE radiative transfer models used to determine production rates and excitation parameters, such as the temperature in the coma. In the inner regions of the coma collisions dominate molecular excitation and the resulting rotational level population is close to LTE. Beyond the LTE inner region, the level populations start to depart from the equilibrium distribution because the gas density is not high enough to reach thermodynamic equilibrium through collisions with neutrals. The inclusion of all relevant excitation processes in cometary atmospheres in a complex 3-dimensional outgassing geometry represents a state-of-the-art coma model which will provide a baseline for interpretation of cometary spectroscopy observations.

The Cowan & A’Hearn (1979) ice sublimation model (sublimation), used to describe comet activity, and common parameters will also be added.

sbpy.photometry¶

The photometry module implements a number of light scattering

models for asteroidal surfaces and cometary coma dust. The goal of

this module is to provide a facility to fit light scattering models to

observed brightness data of asteroids, and to estimate the brightness

of asteroids and cometary comae under specified geometry based on

scattering models. Specifically, we include a number of

disk-integrated phase function models for asteroids, bidirectional

reflectance (I/F) models of particulate surfaces, and phase functions

of dust grains in cometary comae. The disk-integrated phase function

models of asteroids include the IAU adopted (H, G1 , G2) system

(Muinonen et al. 2010), the simplified (H, G12) system (Muinonen et

al. 2010) and the revised (H, G12) system (Penttila et al. 2016), as

well as the classic IAU (H, G) system. The

disk-resolved bidirectional reflectance model includes a number of

models that have been widely used in the small bodies community, such

as the Lommel-Seeliger model, Lambert model, Lunar-Lambert model,

etc. Surface facet geometries used in the different models can be

derived with methods in shape. We also include the most

commonly used 5-parameter version of the Hapke scattering

model. Empirical cometary dust phase functions are implemented, too

(Marcus 2007; Schleicher & Bair 2011,

https://asteroid.lowell.edu/comet/dustphase.html). Some

single-scattering phase functions such as the Henyey-Greenstein

function will also be implemented.

sbpy.shape¶

The shape module provides tools for the use of 3D shape models

of small bodies and the analysis of lightcurve observations. The user

can load asteroid shapes saved in a number of common formats, such as

VRML, OBJ, into Kaasalainen, and then calculate the geometry

of illumination and view for its surface facets, and manipulate

it. Furthermore, Kaasalainen will provide methods for

lightcurve inversion. shape will provide an interface to use

shape models for functions in photometry.

In addition to the shape model methods, shape also provides

methods for the analysis and simulation of simple lightcurve data. The

Lightcurve class provides routines to fit rotational period

(based on Lomb-Scargle routines implemented in stats and other

frequency tools), Fourier coefficients, and spin pole axis

orientation. The class will also be able to simulate a lightcurve at

specified epochs with a shape model class and the associated

information such as pole orientation, illumination and viewing

geometry as provided by the Phys class, and a scattering model

provided through classes defined in the photometry module.

sbpy.spectroscopy¶

As part of spectroscopy, we provide routines for fitting

measured spectra, as well as simulating synthetic spectra over a wide

range of the electromagnetic spectrum. The spectral models include

emission lines relevant to observations of comet comae, as well as

reflectance spectra of asteroid and comet surfaces. The module

provides functions to fit and remove baselines or slopes, as well as

to fit emission lines or reflectance spectra.

In addition to the aforementioned functionality, we provide a class

Hapke that implements Hapke spectral mixing

functionality.

This module also provides spectrophotometry methods as part of Spectrophotometry. This functionality includes the transmission of spectra (empirical, generated, or from the literature) through common photometric filters, and the derivation of photometric colors from spectral slopes with SpectralGradient.

sbpy.thermal¶

Thermal modeling capabilities for asteroids are available through the

thermal module. The module provides implementations of the

Standard Thermal Model (STM, Morrison & Lebofsky

1979), the Fast-Rotating Model (FRM, Lebofsky &

Spencer 1989), and the popular Near-Earth Asteroid Thermal Model

(NEATM, Harris 1998) which can all be used in the same

way for estimating fluxes or fitting model solutions to observational

data.

sbpy.imageanalysis¶

The imageanalysis module will focus on the analysis of

telescopic images. Centroid provides a range of

centroiding methods, including a dedicated comet centroiding technique

that mitigates coma and tail biases (Tholen & Chesley 2004). Code

will also be developed to incorporate ephemerides into FITS image

headers to facilitate image reprojection in the rest frame of the

moving target (moving_wcs) for image co-addition,

e.g., using SWARP (Bertin 2002). We will modify and integrate cometary

coma enhancement code from collaborator Samarasinha

(CometaryEnhancements; Samarasinha & Larson 2014;

Martin et al. 2015). The coma enhancements will be coded into a plugin

for the Ginga Image Viewer.

imageanalysis will also provide PSF subtraction functionality

that is utilizing and extending the Astropy affiliated package

photutils; this class will provide wrappers for photutils to

simplify the application for moving object observations. Results of

imageanalysis.PSFSubtraction routines can be directly used in

imageanalysis.Cometary- Enhancements for further analysis.

sbpy.obsutil¶

The obsutil module enables the user to conveniently check

observability of moving targets and to plan future observations. Using

Ephem functionality, obsutil provides tools to

identify peak observability over a range of time based on different

criteria, create observing scripts, plot quantities like airmass as a

function of time, and create finder charts for an individual

target. These functions and plots will be easily customizable and will

work identically for individual targets and large numbers of

targets. Finder charts will be produced from online sky survey data,

providing information on the target’s track across the sky, it’s

positional uncertainty, background stars with known magnitudes for

calibration purposes, and other moving objects.

sbpy.bib¶

bib provides an innovative feature that simplifies the

acknowledgment of methods and code utilized by the user. After

activating the bibliography tracker in bib, references and

citations of all functions used by the user are tracked in the

background. The user can request a list of references that should be

cited based on sbpy functionality that was used at any time as clear

text or in the LATeX BibTex format.

sbpy.calib¶

sbpy.calib includes calibration methods, including the photometric

calibration of various broad-band filters relative to the Sun’s or

Vega’s spectrum.

Design Principles - The Zen of sbpy¶

In the design of sbpy, a few decisions have been made to provide a

highly flexible but still easy-to-use API. These decisions are

summarized in the Design Principles, or, the Zen of sbpy.

Some of these decisions affect the user directly and might be considered unnecessarily complicated by some. Here, we review and discuss some of these principles for the interested user.

Physical parameters are quantities¶

sbpy requires every parameter with a physical dimension (e.g.,

length, mass, velocity, etc.) to be a astropy.units.Quantity

object. Only dimensionless parameters (e.g., eccentricity, infrared beaming

parameter, etc.) are allowed to be dimensionless data types such as floats.

The reason for this decision is simple: every astropy.units.Quantity

object comes with a physical unit. Consider the following example: we

define a Phys object with a diameter for asteroid Ceres:

>>> from sbpy.data import Phys

>>> ceres = Phys.from_dict({'targetname': 'Ceres',

... 'diameter': 945})

Traceback (most recent call last):

...

sbpy.data.core.FieldError: Field diameter is not an instance of <class 'astropy.units.quantity.Quantity'>

Phys.from_dict raised an exception (FieldError) on ‘diameter’ because it was

not an astropy.units.Quantity object, i.e., it did not have units of length.

Of course, we know that Ceres’ diameter is 945 km, but it was not clear from our

definition. Any functionality in sbpy would have to presume that diameters

are always given in km. This makes sense for large objects - but what about

meter-sized objects like near-Earth asteroids?

Following the Zen of Python (explicit is better than implicit), we require that units are explicitly defined:

>>> import astropy.units as u

>>> ceres = Phys.from_dict({'targetname': 'Ceres',

... 'diameter': 945*u.km})

>>> ceres

<QTable length=1>

targetname diameter

km

str5 float64

---------- --------

Ceres 945.0

This way, units and dimensions are always available where they make sense and we can easily convert between different units:

>>> print(ceres['diameter'].to('m'))

[945000.] m

Epochs must be Time objects¶

The same point in time can be described by a human-readable ISO time

string ('2019-08-08 17:11:19.196') or a Julian Date

(2458704.216194403), as well as other formats. Furthermore, these

time formats return different results for different time scales: UT

ISO time '2019-08-08 17:11:19.196' converts to '2019-08-08

17:12:28.379' using the TDB time scale.

In order to minimize confusion introduced by different time formats

and time scales, sbpy requires that epochs and points in time are

defined as Time objects, which resolve this confusion:

>>> from sbpy.data import Obs

>>> from astropy.time import Time

>>> obs = Obs.from_dict({'epoch': Time(['2018-01-12', '2018-01-13']),

... 'mag': [12.3, 12.6]*u.mag})

>>> obs['epoch']

<Time object: scale='utc' format='iso' value=['2018-01-12 00:00:00.000' '2018-01-13 00:00:00.000']>

Time objects can be readily converted into other formats:

>>> obs['epoch'].jd

array([2458130.5, 2458131.5])

>>> obs['epoch'].mjd

array([58130., 58131.])

>>> obs['epoch'].decimalyear

array([2018.03013699, 2018.03287671])

>>> obs['epoch'].iso

array(['2018-01-12 00:00:00.000', '2018-01-13 00:00:00.000'], dtype='<U23')

as well as other time scales:

>>> obs['epoch'].utc.iso

array(['2018-01-12 00:00:00.000', '2018-01-13 00:00:00.000'], dtype='<U23')

>>> obs['epoch'].tdb.iso

array(['2018-01-12 00:01:09.184', '2018-01-13 00:01:09.184'], dtype='<U23')

>>> obs['epoch'].tai.iso

array(['2018-01-12 00:00:37.000', '2018-01-13 00:00:37.000'], dtype='<U23')

See Epochs and the use of astropy.time and Time for additional information.

Use sbpy DataClass objects¶

Finally, we require that topically similar parameters are bundled in

DataClass objects, which serve as data containers (see

this page for an introduction).

This containerization makes it possible to keep data neatly formatted and to minimize the number of input parameters for functions and methods.